The route we finally chose from Boulder to the Black Hills Wild Horse Sanctuary took us through four states. It was just 5 AM, but the highway leading to and even after Fort Collins was already full of cars and fast moving--faster certainly than my mind considering the hour and lack of sleep I got the night before. Though I had tried hard to get to bed early, my excitement and nervousness kept me awake. This was a huge decision and one I didn’t feel confident making on my own, but I was determined to proceed anyway. I knew this project might be riddled with mistakes; mistakes from which I will likely learn the most.

Several weeks earlier, my trainer, Sean Davies had driven to the sanctuary to pick up two mustangs for a client of his in Texas. She had adopted seven in total, two of which Sean would gentle before sending them down to their new home. Before he left on the trip, I asked him to look through the available horses for any particularly large, drafty ones. He and I had been working through the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) wild horse adoption process for several months and my most recent call to Canon City had not been reassuring: though the government moved quickly out of a brief January shutdown, the contract between the BLM and the Canon City prison was still in negotiations, so all facility adoptions were still on hold. In Colorado and some other western states, the federal government contracts with prisons to store mustangs after they are gathered from various herd management areas. At many locations, inmates train some of the wild horses to be auctioned. When I first started calling around, I was told that there were at least 800 wild horses held at Canon City and I had hoped to get there to walk the pens to select one that had not yet been handled. The horses were still there, but when I asked about when we might come to see them, the site director replied,“Maybe March.” His response was maddening. There are thousands of mustangs in holding or storage in the U.S., yet since November, Sean and I had tried fruitlessly to find one to adopt from a BLM facility; there were roadblocks at every turn. My timeline for a January- June training with Sean was already cutting it close. I realized that if we didn’t figure out something soon, my role in the training was going to be small if anything at all and the being a part of the entire process was essential to the project. I needed to learn his approach and how to further it once this horse and I are on our own.

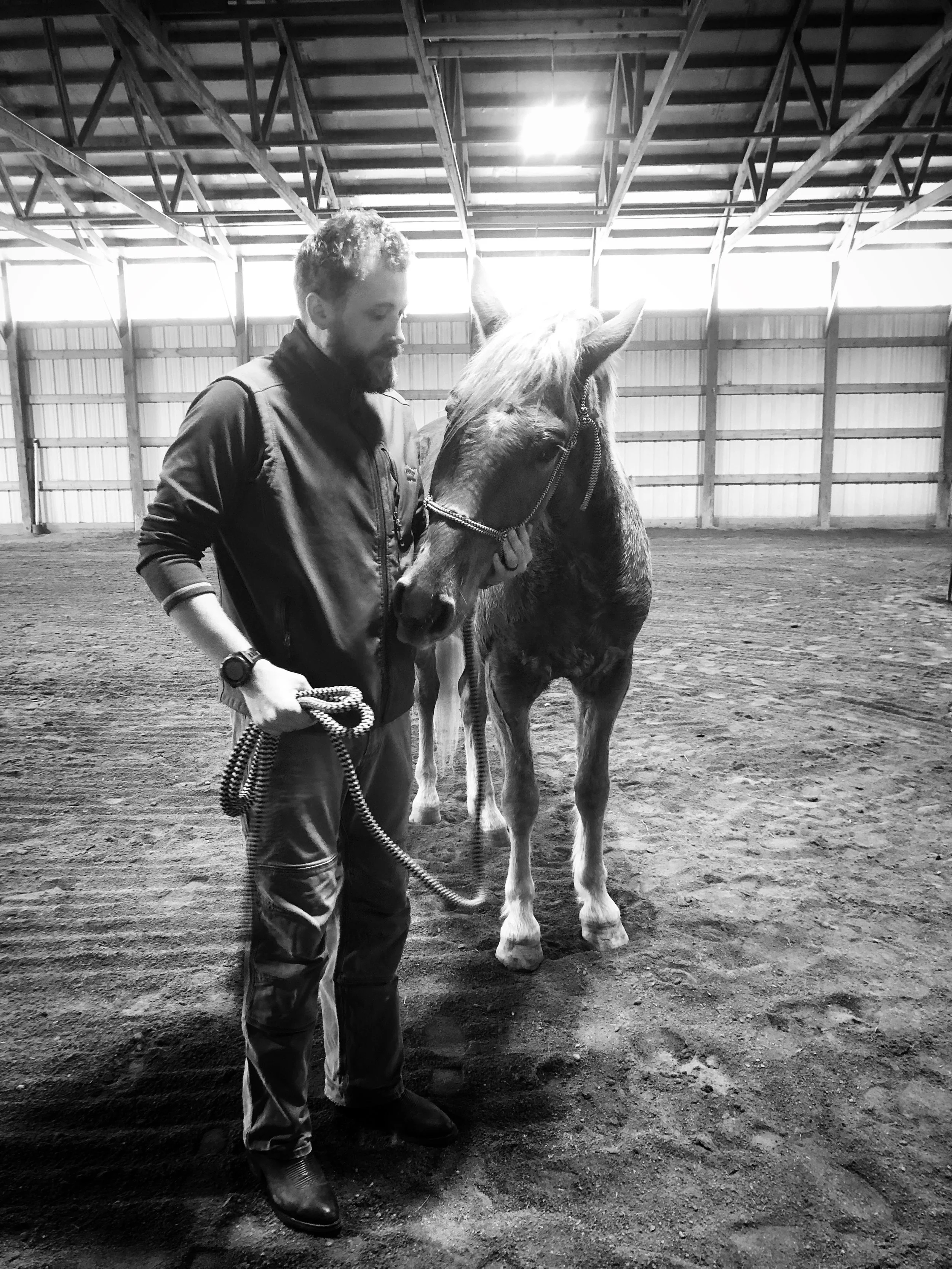

Sean sent me photos from his visit to Black Hills, noting that there were about 20 available horses to consider. At least one gelding was larger than the others, and this coming two-year-old seemed to have the personality we were seeking. Jason, who works at the sanctuary, referred to him as a horse who might someday be “a child’s ride.” The gelding had “that kind of mind.” Sounded perfect. So, I found myself two weeks later taking the day off work, convincing my son to split the drive with me, and heading north several hours before a Monday sunrise.

The wind picked up as we got closer to Fort Collins. I had heard it at the ungodly hour I got out of bed but tried to ignore it, hoping it would subside. Wind was something I never considered when I lived out east. In Colorado, mention of “high winds” in the news took on an entirely new meaning for me. While in New York it might mean a few downed power lines, I saw an accident soon after to moving to Boulder in which an exit sign had blown off its post and crashed through a car windshield. Winds here are no joke. The gusts rallied in earnest after Fort Collins and the view out my windshield looked like something out of a video game or Star Trek movie, with tumbleweeds shooting across the road and sometimes sucking violently under my car. Jake slept through it all as I tapped on the steering wheel reminding myself that a Subaru Outback was a pretty safe vehicle for these conditions. It is the larger profile trucks and trailers that one needs to worry about.

As we approached the Wyoming border, illuminated signs warned of high wind restrictions for larger vehicles and unweighted trailers. I was reassured by this because it meant no eighteen wheelers on Route 25. Driving among them during 60+ mile per hour gusts was not the thrill I was looking for this morning. I was already worried about staying alert for the drive; I didn’t want to have to stay even more alert because of potential hazards. Most importantly, though, I didn’t want to be nervous about all this--and I certainly didn’t want my 20-year-old son to sense it. (If you are wondering, they always do). All that considered, just after passing the exit where all restricted vehicles filed off, I wondered how often, really, something actually happened due to these types of winds. Five minutes later I had my answer: a white tractor-trailer slumped on its side across the median with newly placed caution tape across its front. All right then, I thought and slowed down a bit.

Once we got to Nebraska, things calmed down, wind-wise and road-wise. The rest of the drive would be on relatively small state highways, some rougher than others. The weather was clear at first, so we made good time. Midway through Nebraska it began to rain, but I didn’t worry because it was about 40 degrees. I couldn't imagine it dropping that much as we moved north, especially heading into the sunlight of the day. As if to remind me of my naivete, the temperature progressively dropped as we moved on, and by the time we were driving through the Ogala National Grassland it was snowing and there was a substantial layer of ice on the road. Luckily, we were the only ones on it and I was able to relax, distracted by the beauty of the white covered hills that rose on either side of the remarkably straight route we traveled. With the clouds, the morning light was slowly spreading, lending a subtle pink hue to the landscape and sky.

Jake woke up for the last stretches of grassland in time to see the abandoned town of Ardmore, which I have since learned has been a ghost town since 2014. It’s most recent census in 1980 recorded 18 residents. Flanking either side of Route 71 just a mile north of the Nebraska-South Dakota border, it appears as if one day all the folks that lived there just decided not to come home. There are cars parked in driveways and others rusting out in backyards. Doors to some of the houses lie haphazardly open and curtains inside windows ruffled as we drove past. One gets the eerie sense that no one is there yet if you were to walk into one of the houses it wouldn’t be shocking to encounter someone. It was strange and beautiful and it seemed a perfect place to take photographs. As I considered this, I also couldn’t help feeling ridiculous; when I saw the dot and label on the map when planning the drive, I had considered Ardmore as our stopping place on the way home, one where I would be able to host a work conference call. Ardmore definitely did not have a Starbucks and from what I could see on my phone there was no service of any kind. We would have to return at some point to explore this place, but aware of how much longer the drive had already taken than I expected, we kept going. Though picturesque, the rest of the drive was uneventful. We stopped quickly at a gas station in Rumford, a small town about an hour from the sanctuary, grabbed coffee, used the restroom and headed north towards Hot Springs.

The signs for the Black Hills Wild Horse Sanctuary start about 4 miles from the turn-off of Route 71D, which, given the scale of things, makes a lot of sense. In the west, everything seems larger to this easterner: the sky, the roads and the spacing between destinations. About a mile up the sanctuary road we spotted them--the first group of wild horses in a pasture, some leaning lazily up against the fence as if waiting for visitors. I was struck by how quiet they seemed and then by the variety of colors in the herd. I learned later that many Spanish mustangs are a bluish “grulla” color, with manes that in the right light shine purple. They were beautiful, but I noticed that most in this group were small in stature, almost ponies. For the first time I worried that they might not have any horses near the size I had hoped for and I considered whether I needed to start adjusting my expectations.

American mustangs, in general, are not large. Many of the populations are descendants of the original European explorer’s horses, though over the centuries other captive horses have escaped from ranches and joined the genetic pools. As a result, there are characteristics that define different types of mustangs, some of which have specific names while others are just referred to by their region of origin. In my research looking for a horse to adopt, I learned that the larger, stockier mustangs are often found in the Salt Wells areas in Wyoming. Draft horses that used to work the farm soil in those regions mixed in with the wild horse bands, increasing the average sized animal and also producing some specimens that are upwards of 16 and even 17 hands. I had tried to locate Salt Wells horses in holding and found that though there were some available at a facility in Rock Springs, Wyoming, they were predominantly mares from a recent gather. I was warned that there was a 90% chance they were pregnant, which quickly eliminated that option. I wondered as we continued down the drive if any of the mustangs at the sanctuary might be of Salt Wells origin or some other area with larger stock.

The sanctuary proper looks something out of a movie set, and it has, on a number of occasions, been used as one. The main buildings are original ranch buildings from when it was first settled in the early 1900s. What were once used a lambing sheds, necessary to protect what are more fragile creatures in the harsh South Dakota landscape, are now the chicken coops. The old tack building is used for storage. The office sits behind what was the original homestead house, which now functions as a gift shop. As Jake and I slid around on the snow, we met one of the organization’s volunteers, who led us to the office where we would wait for Susan, the program director and, according to a news article featured on the sanctuary’s website, the energy behind the whole operation. With no cell service, we had no way to alert her to our arrival and she was down at more recently built main farmhouse where she lives and cares for the sanctuary founder who is now in his 90s. This pause gave Jake and me a chance to read some of the literature posted in the waiting room, to watch the what seemed an endless gaggle of wild turkeys perched and pecking around the closest paddocks, and to skim through scrapbook pages with photographs of various horses and humans of note in the sanctuary’s history. I realized that I needed to learn more about Dayton O. Hyde, the sanctuary founder. A poster for a movie about Hyde’s life hung prominently in the waiting area. Sean had mentioned Dayton O. Hyde, but I didn’t realize he was still living on the property, though as I learned more about his life later when I finally saw the film, it’s clear there is no place he would rather be.

I wasn’t sure whether Susan would be the one to take us to meet the adoptable horses or if Jason, one of the handlers, would do it. I had met Susan a week earlier when she came down to Boulder to hear journalist David Philipps talk about his newly published book Wild Horse Country, which I had heard about in an NPR interview and immediately read. It was the culmination of reading the book and boarding my horse at Sean’s that gave me the idea to learn how to gentle and train a mustang. So, the coming together of all pieces at the reading seemed serendipitous. When she arrived at the office, Susan told us to wait outside for her to pull around in the truck and to be careful on the ice as we walked out. I laughed, looking down at her slick soled Ugg boots, but realized that regardless of how treacherous her footwear seemed, she had been successfully navigating this winter landscape for 21 years and today was not going to be any exception.

Susan’s truck has a full cargo cab, so all six feet of Jake fit comfortably in the back seat. He got his camera ready as we drove over to the first pasture where the yearlings, two and three-year-olds live. They seemed interested but not terribly affected by our approach as we drove slowly into the field. Two thin brown lines of hay striped parallel, serving as both food and, judging by the horses bedded down here and there, insulation from the weather. “In cold like this,” Susan noted in her southern drawl, “they sometimes mistake their groceries for beds.” As we got closer the truck seemed to pique the horses’ interest. The sanctuary folks feed out the back of it so within minutes we were surrounded by pushy adolescent horse faces, some more insistent than others. Several of the mares started eating snow off the hood, while a few others discovered that the side mirrors were at a perfect height for ear and neck scratching.

“Don’t let him do that!” Susan insisted. “We replaced that mirror last month.” She paused. “For just that reason.”